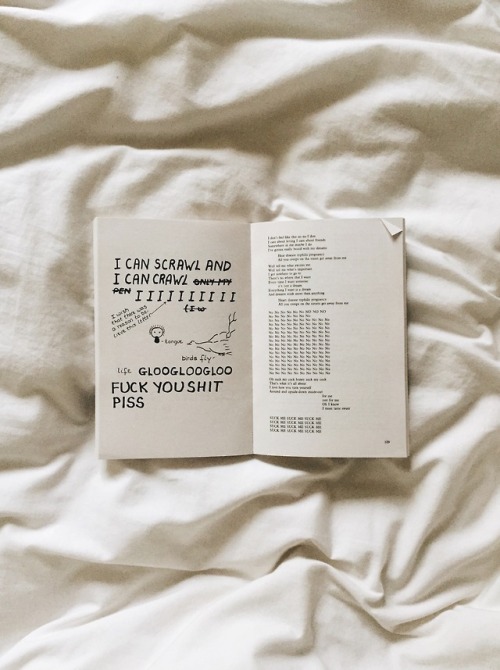

‘I was bent upon getting over a perspective of barriers, with my hands and feet bound. The reader becomes an audience to reels of different times, places and events, a retracing of the character’s history, whilst simultaneously a retracing of literary history. Thus, pages are filled with fragments of shock, familiarity, and unfamiliarity. She skillfully challenges the formulaic character studies - literary novels can tend to be by playing with time, sexes, and identities. Pip (named Peter in Acker’s novel) is the vehicle for literary experimentation to its fullest – so much so, that some have accused Acker of plagiarism, but is it an accusation when it is completely deliberate? Acker with her postmodernist-punk attitude aimed to transgress literary convention, challenging focalisation (reminding the reader the main narrator is fiction and not the writer) whilst also breaking the bounds of literary style, flowing in and out of prose, poem, and script. Acker writes with a postmodern twist with an almost post-feminist allegiance, portraying patriarchal structures in a way which at first reading endorses them but to fully subvert them. Two different cities, two different eras, but two very similar experiences of the desire for transcendence, a desire to reach beyond their current planes. With the added twist of exploring it through Charles Dicken’s classic of the same name which paints the grittiness of London of the nineteenth century. This isn't an expression of a real thing: this is the thing itself.Īcker witnessed the grittiness of New York City in the eighties, and like other writers of the time took advantage of the ability to write about it. And without this living there is nothing this living is the only matter matters. If everything is living, it's not a name but moving.

And she was given the real names of things' means she really perceived, she saw the real.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)